New research has stated that rat control should be considered an urgent conservation priority on remote tropical islands to protect coral reefs.

An international team of scientists, led by Professor Nick Graham of Lancaster University, conducted a study into the ecosystems in the northern atolls of the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, and their work has revealed that invasive rats decimate seabird populations on tropical islands, and this has direct and dire consequences for the coral reefs surrounding these land masses.

The paper (Seabirds enhance coral reef productivity and functioning in the absence of invasive rats), which has been published in the journal Nature, shows how invasive predators such as rats – which feed on bird eggs, chicks and even adult birds – are estimated to have devastated seabird populations within 90 percent of the world’s temperate and tropical island groups, but until now the extent of their impact on coral reefs wasn’t known.

Professor Graham explained: “Seabirds are crucial to these kinds of islands because they are able to fly to highly productive areas of open ocean to feed. They then return to their island homes where they roost and breed, depositing guano – or bird droppings – on the soil. This guano is rich in the nutrients, nitrogen and phosphorus. Until now, we didn’t know to what extent this made a difference to adjacent coral reefs.”

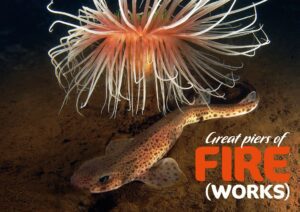

An extraordinary set of remote tropical islands in the central Indian Ocean, the Chagos islands provided a perfect ‘laboratory’ setting as some of the islands are rat-free, while others are infested with black rats – thought to have been introduced in the late 1700s and early 1800s. This unusual context enabled the researchers to undertake a unique, large-scale study directly comparing the reef ecosystems around these two types of islands.

By examining soil samples, algae, and counting fish numbers close to the six rat-free and six rat-infested islands, scientists uncovered evidence of severe ecological harm caused by the rats, which extended way beyond the islands and into the sea.

Rat-free islands had significantly more seabird life and nitrogen in their soils, and this increased nitrogen made its way into the sea, benefiting macroalgae, filter-feeding sponges, turf algae, and fish on adjacent coral reefs.

Fish life adjacent to rat-free islands was far more abundant with the mass of fish estimated to be 50 percent greater.

The team also found that grazing of algae – an important function where fish consume algae and dead coral, providing a stable base for new coral growth – was 3.2 times higher adjacent to rat free islands.

“These results not only show the dramatic effect that rats can have on the composition of biological communities, but also on the way these vulnerable ecosystems function (or operate),” commented co-author Dr Andrew Hoey, from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies in Australia.

Professor Graham concluded: “The results of this study are clear. Rat eradication should be a high conservation priority on oceanic islands. Getting rid of the rats would be likely to benefit terrestrial ecosystems and enhance coral reef productivity and functioning by restoring seabird derived nutrient subsidies from large areas of ocean. It could tip the balance for the future survival of these reefs and their ecosystems.”